While a breakthrough hasn’t happened yet in Washington’s debt-ceiling standoff, there is increasing chatter about what could go into a bipartisan deal that ends the stalemate and avoids a market-shaking default.

“The centerpiece of an obvious deal would be a two-year cap on discretionary spending, somewhere in between the president’s 6% proposed increase and the Republicans’ 9% proposed cut,” said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the conservative-leaning Manhattan Institute who focuses on budget, tax and economic policy.

“Both sides need to come to a discretionary top-line figure in the next couple of weeks to begin the appropriations process anyway, so they may as well put that into the debt-limit negotiations,” Riedl told MarketWatch.

“By doing this, both sides can claim victory by moving the other side off of their position on discretionary spending,” added Riedl, who previously was a top staffer for former Ohio GOP Sen. Rob Portman. “It’s easy to pass. It’s a one-page bill that could be drafted in 30 minutes.”

Other parts of the possible deal are expected to center on energy-permitting reforms and unused COVID-19 aid.

Second meeting expected Tuesday

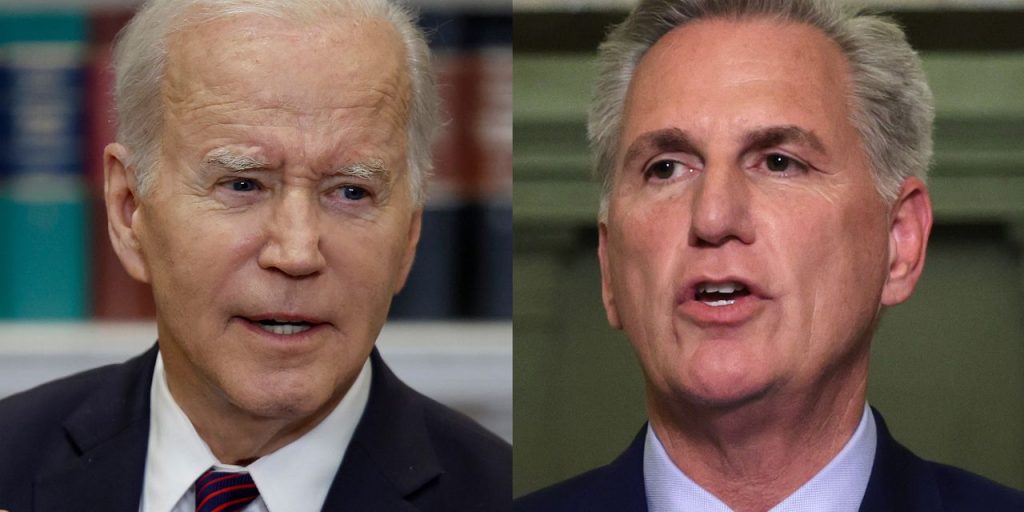

The second round of debt-ceiling talks between the White House and the top four U.S. lawmakers appears set for Tuesday, President Joe Biden said Sunday.

The group first met on May 9, with Biden describing the parley as “productive,” while House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said he “didn’t see any new movement.”

McCarthy on Monday said he’s still “far apart” from the president on reaching a deal to raise the debt limit.

The president and the four lawmakers had planned to meet again on Friday, but the meeting was postponed. A source familiar with the meetings called the delay a positive development, as staffers are continuing to work.

McCarthy and his fellow Republicans have been demanding spending cuts in exchange for raising the ceiling for federal borrowing, while Biden and his fellow Democrats have said the lift should be made without conditions.

Short-term move looks possible

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned on May 1 that a U.S. default could happen as soon as June 1 if Congress doesn’t raise the federal government’s borrowing limit. The Bipartisan Policy Center and Congressional Budget Office have each offered similar projections.

Due to a “compressed calendar” and outstanding questions on the potential deal, the most likely outcome is that Washington will deliver a short-term extension for the debt limit by June 1, according to Chris Krueger, managing director at TD Cowen’s Washington Research Group.

“Given the lack of time, we still anticipate the need for a very short-term hike of the debt ceiling as well as likely changes to the Congressional schedule (Senate supposed to be on recess next week),” Krueger wrote in a note on Monday. “September is likely the key month for clarity on both discretionary spending and the permitting-reform details.”

Biden said he’s not ruling anything out besides default when he was asked last week about a short-term increase for the federal borrowing limit that would provide his administration and Congress with more time to come up with a long-term solution.

‘Permitting reforms and COVID rescissions can be relatively bipartisan’

GOP Rep. Garret Graves of Louisiana, a key ally of McCarthy, said last week that House Republicans believe there is room for an agreement that involves permitting reform, rescinding unspent COVID-19 funding, limits on discretionary spending and work requirements for some recipients of federal aid, according to multiple published reports.

Biden, meanwhile, sounded open to clawing back some unspent COVID-relief funds as he took questions from reporters following his much-anticipated meeting Tuesday with the top four U.S. lawmakers.

“We don’t need it all,” Biden said. “I have to take a hard look at it. It’s on the table.”

On Wednesday, the Biden White House released a statement outlining its priorities for permitting reform.

“Permitting reforms and COVID rescissions can be relatively bipartisan additions to the package to broaden its appeal and scope, but anything related to the Inflation Reduction Act — such as the energy-tax credits or [Internal Revenue Service] funding — has no chance of making it into a bipartisan deal,” the Manhattan Institute’s Riedl said. “Work requirements are also going to prove too toxic for Democrats to be part of a deal.”

Analysts have said it’s key for Democrats to negotiate a budget deal along with a debt-ceiling hike but to make it seem like the ceiling was not a part of the budget talks, while for McCarthy it’s important to make it seem like he did leverage the borrowing limit for fiscal concessions.

“The good news” is that the meeting on May 9 “kicked off what will be back-channel staff negotiations between the White House and congressional leadership,” Riedl said.

“Unfortunately, however, both sides are probably going to continue playing chicken up until the last minute, because they believe they will have the upper hand if it comes down to the very end. So I think, unfortunately, this is going to go on for a little while.”

Biden criticized the Republican stance on the debt-ceiling standoff as he delivered a speech last Wednesday in New York’s Westchester County. His planned trip there has been viewed as an indication that the White House wasn’t expecting a big breakthrough at the May 9 meeting.

“If we default on our debt, the whole world is in trouble,” the president said.

In August 2011, lawmakers approved an increase to the limit just hours before a potential government default. Within days, the U.S. lost its triple-A debt rating from S&P for the first time in history, with the credit-rating company saying the American political system had become less stable.

U.S. stocks

DJIA,

SPX,

plunged in August 2011 following that downgrade from S&P.

Now read: Debt-ceiling solution? The 14th Amendment, explained.

Also: Biden blasts Republicans for tying debt ceiling to budget, while GOP says Democrats did the same thing

Plus: ‘This is an especially inopportune time to have a political debate over the debt limit,’ warns economist Mark Zandi

Read the full article here