A version of this story appeared in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here.

Theodore Roosevelt carefully crafted his image of rugged manliness. The wealthy heir became a Badlands cowboy and a volunteer Rough Rider and war hero.

A populist and a reformer as president, Roosevelt enjoyed incredible popularity during his lifetime – and he nearly remade the American political system when, frustrated by the direction of the Republican Party after his presidency, he splintered off as a third-party candidate and nearly won election as a Progressive “Bull Moose” in 1912.

But that image is not complete, according to “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Created a President,” a new biography by Edward O’Keefe, CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation, which is constructing a new Roosevelt library in the Badlands of North Dakota. O’Keefe is also a former colleague at CNN.

The book argues that the women in Roosevelt’s life do not get the historical attention they deserve, something O’Keefe proves with detailed research and engaging writing.

I talked to O’Keefe about the book and how Roosevelt and his definition of masculinity relate to today. Our conversation by phone, edited for length, is below:

WOLF: Your book is about the women behind the most notoriously masculine president. What were you trying to do here?

O’KEEFE: “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt” argues that the most masculine president in the American memory is actually the product of unsung and extraordinary women.

Theodore Roosevelt is chiseled in marble on Mount Rushmore, and the myth is that everything he did in his incredibly successful personal and political life was the product of his own will. That is true, but it also isn’t the full story.

His two sisters, Bamie (Anna) and Conie (Corinne); his two wives, Alice and Edith; and his mother Mittie (Martha) were an integral part of his success, and their stories have been almost entirely lost to history.

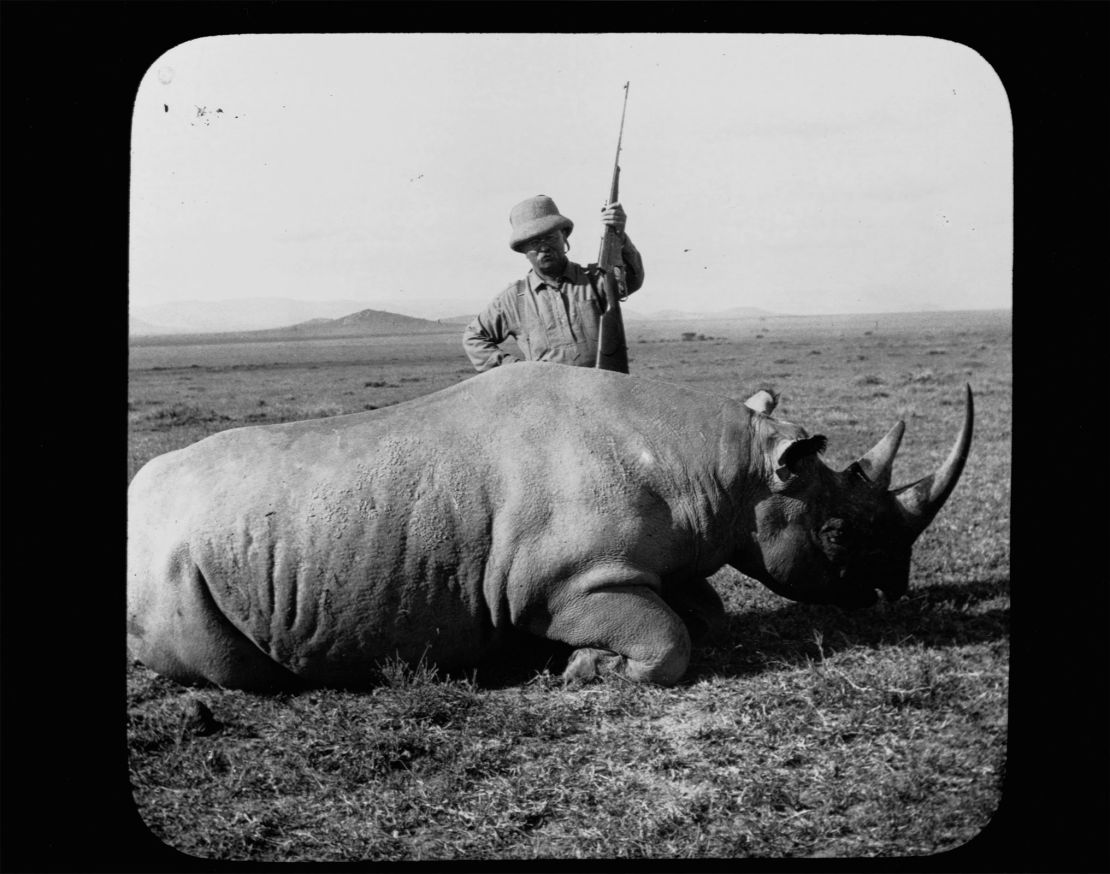

WOLF: That theme shines through — that these women propped up this most famous of American men. But much of his life is built around leaving them. He was not there when his first wife gave birth. He left his second wife, who was critically ill, to go off with the Rough Riders. He’s on safari. He’s in the Badlands. He’s very absent. How do you reconcile that fact with the larger theme of the book?

O’KEEFE: I’m so glad you noticed that. I had this fascinating conversation with Connie Roosevelt, who is the wife of Theodore Roosevelt IV (Teddy’s great-grandson).

The first time I met her in 2019, we were at a fundraiser for the National Parks Conservation Association, and I had just started to work on the research for what would become “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt.” And I said to Connie almost exactly as you’re saying, that there is this pattern that Theodore Roosevelt is absent. He leaves in a lot of emotionally difficult circumstances.

And she chuckled and said, “When the going gets tough, the tough go hunting,” which is a line that I do use in the book. Theodore Roosevelt, who is known for willing himself through physical pain — that resilience of a cowboy and a rancher would really wilt when it came to emotionally difficult circumstances.

He basically abandoned his daughter for the better part of three years, offered to give his daughter to his sister and have Bamie, his elder sister, raise her. He later said of his exploits in Cuba that he would have left his wife’s deathbed to be there, and that’s not an exaggerated statement.

I think that the women in his life understood that they needed to be the support system, especially emotionally, that he didn’t always have the capacity to have. I think if there’s one surprising thing in “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt,” in addition to the argument that TR is actually the product of women, it’s that he’s an incredibly emotional person, as much as he’s caricatured in history.

I love Robin Williams and the depiction in “Night at the Museum,” but that’s a cartoon of Theodore Roosevelt. It’s easy to caricature him with the big smile and teeth and the hat and the cowboy, but he’s a very sensitive, emotional person who feels very deeply.

I think it’s what allowed him to empathize with people. It’s what allowed him to connect with people. That’s all, by the way, a direct result of the influence of his mother, Mittie, who’s been completely written off in history.

WOLF: The gender inequality of the day is a major takeaway from this book. But also the general inequality. Roosevelt was born into fabulous wealth. These are people that take monthslong trips to Europe when he’s a child. He is never not wealthy. But then he escapes that perception to become this populist leader. When inequality is such a big issue today, how do you view his rise from that perspective?

O’KEEFE: Theodore Roosevelt is not a Horatio Alger story. He does not rise from humble beginnings to find his way to the upper echelons of power and wealth in America.

Interestingly, the expectation in the Victorian and Gilded Age was that those with the greatest amount in society owed very little back to the people. Theodore Roosevelt, like his distant cousin Franklin Roosevelt, was considered a traitor to his class. It was very unusual for someone of his status and wealth to run for office.

Politics was seen as a dirty business, something that the middle and lower classes, that the immigrant class would be interested in, because why would you need the power of the vote? You have wealth. You have influence.

I think some of that is due to the influence of his parents, Mittie and Thee (Theodore Sr.), a Southerner and a Northerner, who were able to disagree without being disagreeable over one of the most contentious issues in American memory, the Civil War. He saw them come together as a family and be interested in the unity of their family as well as the country.

He did have a noblesse oblige. He did feel that to whom much is given, much is required. And I think that experience out in the Badlands of North Dakota — where it didn’t matter if you were wealthy; you were expected to work equally with the person alongside you. A horse in a roundup doesn’t much care if you’re from the East Side of Manhattan — you’re either gonna survive and do the work or you’re not gonna make it.

WOLF: The most gripping part of the book is your description of the circumstances around his first wife dying in childbirth and his mother dying in the same house on the same day. I was trying to quantify that level of tragedy, and the first thing that popped to my mind was the current president, Joe Biden, who lost his wife and his daughter just after he was first elected to the Senate. I wonder if you also made that connection.

O’KEEFE: Absolutely. Loss which no one ever hopes to experience is often the crucible of an individual’s life.

In Theodore’s circumstance, it was his mother, Mittie, after his father’s death, that said, we need to live for the living, not for the dead — that you would dishonor the memory of those who are gone if you did not live a life of purpose.

I think that’s very similar to President Biden’s circumstances, absolutely. You know, he took the seat in the Senate that then, of course, he held for 36 years, in part because it would be a dishonor to the memory of his wife and daughter if he didn’t.

Loss and happenstance, fate and serendipity play such an incredible role in American history. You have to look at these moments, these crucible moments, as the turning points of not just these individual political lives but how they intertwine with the fate of the nation.

WOLF: There’s been a rise recently, particularly on the American political right, of men trying to reassert masculinity. Josh Hawley, the Missouri senator who wrote a book about Roosevelt, more recently has a book called “Manhood,” for instance. What do you think Roosevelt would make of that trend?

O’KEEFE: It’s exactly what he was experiencing at his time. When Roosevelt was born in 1858, there’s no electricity, there’s no cars, there’s no airplanes, there’s no submarines. He will be the first president to go up on an airplane, to ride a car, to travel abroad while president, to go in a submarine.

Everything changes, right? The society is shifting from agrarian to industrial. The technology that is coming in this age is disrupting how people feel about their sense of self and connection and community. There’s an immigration wave in the country that, in the view of many, is changing what the definition of what an American is, and there’s a fierce debate about whether we’re an isolationist country, or we’re going to be a global power.

Does any of this sound familiar?

This all intersects with masculinity and gender roles, right? There are constant themes of masculinity. How to be a man. What does it mean to be a man. What do you have to physically do in order to show that you’re a man.

He’ll project the quintessential ideal of manhood in society’s expectations at the turn of the 20th century. But what I’m showing in “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt” is that he too had this incredible emotional, soft side — that it was women, who were constrained by the age, working with him to achieve his goals.

To your question about what is happening now, people trying to understand gender roles, masculinity, manhood — instead of looking at it as a continuum, trying to sort of define it as one or the other, to me, it sounds very much like something I’ve heard before, if you pay attention to history.

WOLF: There’s a moment in the book when Roosevelt has just had a falling-out with Edith, his childhood sweetheart, who would later become his second wife. He’s riding his horse home and, in a moment of pique, shoots a neighbor’s dog. As I was reading that passage, I immediately thought of South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, who has faced serious backlash for writing in her memoir about shooting a family dog who was unruly. Obviously, the 19th century was a different time, but I wondered if you thought of Roosevelt when you read about Noem, a Dakota lawmaker. Is she not just living “the strenuous life?”

O’KEEFE: There’s a stark difference between a family pet, as described by the governor of South Dakota, and an animal running in the Oyster Bay woods (in New York) that was owned by a neighbor.

But this is the duality of Theodore Roosevelt. If you go out to Sagamore Hill (Roosevelt’s home), to this day, one of the most touching parts is the pet cemetery, where they’ve got the graves of all the different, many beloved animals that they had.

The Roosevelts had a menagerie, a veritable zoo at the White House — Josiah the badger and Emily Spinach, the snake whom Alice (his daughter, who was named for her mother) named because she didn’t like her aunt, Emily, and she didn’t like spinach, so her snake must be Emily Spinach; Algonquin, the pony who was taken up to the second floor of the White House.

They had so many dogs in their home, both in Sagamore and in the White House, that the pet cemetery is filled with the names of these beloved family pets.

So it’s incongruous with Theodore Roosevelt’s attitude about pets and animals, but yes, it is true that after he broke up with Edith, he was so angry that he did indeed shoot a dog on a horseback ride through the woods around Oyster Bay. An unusual parallel, perhaps, to today’s stories.

Read the full article here