Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

A heated online debate on the definition of sexual harassment has broken out in China in the wake of a series of allegations made against an influential screenwriter, rekindling interest in the country’s struggling #MeToo movement.

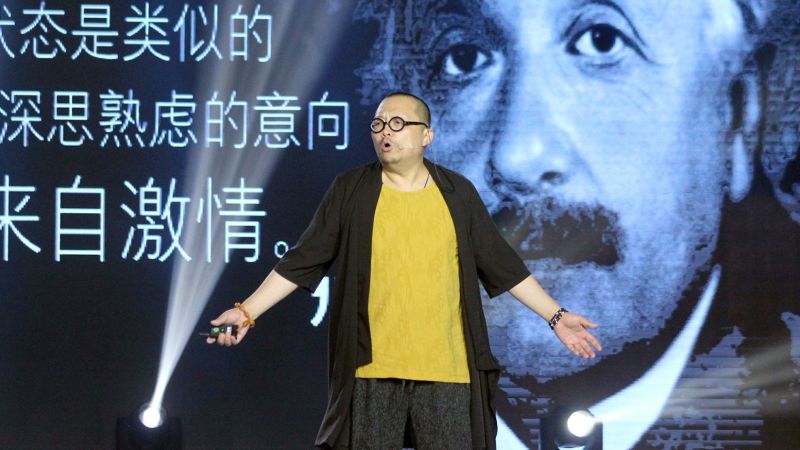

Shi Hang, 52, a well-known figure in China’s media and literary circles, lost work with several businesses, after more than a dozen young women came forward with allegations of sexual harassment against him.

The controversy has underscored the resilience of China’s #MeToo movement, which has suffered frequent setbacks due to censorship and an ongoing crackdown on feminist activism.

In a string of social media posts and interviews with Chinese state media, Shi’s accusers – who did not reveal their real names – described a pattern of alleged misconduct that ranged from sexually suggestive remarks to groping and kissing, in incidents reportedly spanning over a decade.

Shi has strongly denied the accusations of sexual harassment in two separate statements and claimed the encounters were consensual.

“I have never imposed against a woman’s will, nor have I used my so-called powerful position to violate anyone,” he wrote last week on Weibo, China’s highly restricted Twitter-like platform, where he boasts three million followers.

In his defense, Shi also posted selected screenshots of conversations with his accusers, which appear to show they did not object to his flirtatious remarks.

His accusers later rebutted his defense, saying the stark power imbalance between them – a well-established and respected name versus young fans and women looking to break into the industry – made it difficult to push back against Shi.

“As the party with more power, Shi Hang till this day still believes he can be the one to define what is ‘appropriate’ and what constitutes sexual harassment,” five of his accusers said in an online statement, reported by multiple state media outlets. “This is precisely the conventional thinking of those with power.”

Shi and the accusers did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment.

The allegations have since sparked furious debate on Chinese social media, with related hashtags trending for days and racking up hundreds of millions of views on Weibo.

Some users defended Shi and referred to the encounters as “just flirting.” Others rallied to support Shi’s accusers, arguing entrenched gender inequality has created a culture that normalizes sexual harassment against women.

Dai An, a feminist in the southwestern city of Chengdu, said Chinese women have become more willing to speak up. “It’s a different era now, and the environment that was once acquiesced has changed,” she told CNN.

“Women don’t want to be silent anymore, and they don’t want to tolerate men using sex as an outlet to showcase their power.”

Several businesses have since cut ties with Shi, who also reviews books and movies, and makes guest appearances at cultural events and on variety shows.

Xiron, a publishing house in Beijing, announced it would remove a book endorsement by Shi from “Fang Si-Chi’s First Love Paradise,” which tells the story of a 13-year-old girl being coerced into sex by her teacher. The book became an influential part of Taiwan’s #MeToo movement for its themes of power and vulnerability.

Other businesses that have terminated deals with Shi include New Weekly, a Guangzhou-based news magazine, and a bookstore and a theater in the capital Beijing.

It is believed to be the first time that a number of Chinese organizations have publicly terminated their relationship with a celebrity due to alleged sexual harassment, said a prominent Chinese feminist, now based in New Jersey, who did not wish to be named.

“This undoubtedly shows that feminists are more powerful than ever in driving public opinion, and therefore in creating pressure on institutions to give in,” she added

But the public pressure succeeded only because these institutions could not resort to the protection of censorship and government support, the feminist added.

China’s #MeToo movement has long been censored and suppressed by the Chinese Communist Party, which views with suspicion any grassroots organizing that challenges its monopoly on authority.

In recent years, several prominent feminist activists have been silenced and detained. One of them, Huang Xueqin, has been accused of “inciting subversion of state power” and held in jail for 600 days.

In the latest scandal, the allegations against Shi appeared to have largely escaped censorship, but other #MeToo cases targeting officials and prominent state-affiliated figures have been muffled.

Peng Shuai, a Chinese tennis star, was promptly silenced after she publicly accused former Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault on social media in 2021. While Zhou Xiaoxuan, a former state television intern who accused and sued star presenter Zhu Jun of groping and forcibly kissing her was repeatedly blocked on Chinese social media platforms.

China’s #MeToo movement did have its rare legal victories. Last year, Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu was sentenced to 13 years in prison for rape, following allegations made by an 18-year-old Chinese student. The swift arrest of Wu coincided with a broader crackdown by the government on the country’s entertainment sector.

But more often, China’s #MeToo victims who chose to fight their alleged abusers in court faced grueling legal battles. Last August, a Chinese court rejected an appeal by Zhou, the former state media intern, putting an end to her years-long landmark case and dealing a severe blow to the movement.

China did not specify sexual harassment as a legal offense until 2021, when it enacted a civil code defining sexual harassment for the first time in the country’s law.

The code states that an individual can bring a civil claim against a person who engages in sexual harassment toward them “in the form of verbal remarks, written language, images, physical behavior or otherwise,” against their will.

But still, the failure of sexual harassment lawsuits – like Zhou’s – in recent years has made it “increasingly clear that seeking legal remedies for sexual harassment is not realistic,” said the Chinese feminist in New Jersey.

“The victims in [Shi’s] case clearly learned lesson that there is little hope of success in reporting to the police or filing a lawsuit.”

On Chinese social media, some of Shi’s supporters have questioned why his accusers did not call the police.

Xiao Mo, one of Shi’s accusers, said in a lengthy Weibo post that calling the police is not the “best solution to all problems,” especially given that she only realized she had been sexually harassed a few years after it happened.

“Even if I reported it, and he was summoned to the police station, how many days can he be detained for sexual harassment?” she wrote. Xiao Mo, declined CNN’s request for an interview.

“Our core appeal is not legal punishment, but to expose the truth about him so that righteous people can draw their own conclusion in their hearts.”

Read the full article here